Ephesians 2:11-22

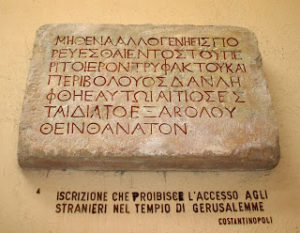

In 1871 two archeologists found a piece of engraved stone from the Jerusalem temple with Greek writing on it. It held a stern warning: “No foreigner is to enter the barriers surrounding the sanctuary. He who is caught will have himself to blame for his death which will follow.”

This was one rule they were, evidently, pretty strict about. No gentiles were permitted to enter the temple. But it was not the only rule. There were degrees of acceptability in the temple worship of the time.

The outermost area of the temple was called the court of the gentiles, and it was a large, open, public area. Anyone could come into the outer court. But within this courtyard there was a barrier, called a soreg, which surrounded a wall defining the perimeter of the outer court of the temple. The outer court was also called the court of the women, because this was as far as Jewish women were allowed to enter. Further within, there was an inner court, the place where the burned sacrifices were made. Jewish men were permitted to enter the inner court, as long as they didn’t have certain conditions that would make them disqualified. And finally, the innermost region, called the Holy of Holies, where only the purest ones could enter.

When you read the Old Testament you notice that there were many types of people who were restricted from participating in temple worship. Foreigners, or those of mixed race; women; eunuchs; anyone with a skin disease; these were all barred from entering. But additionally, Jewish men who were deformed in some way were prevented from entering the inner region. The scriptures speak of the blind and the lame, dwarves, and hunchbacks, all excluded. Anyone judged to have abnormalities or imperfections, excluded. There were many ways a person could be shut out.

We talked a bit last week about insiders and outsiders, and the ways we tend to separate the world into these two categories. The human mind likes order, and if we can’t find it in the world around us, we will create it and impose it. We divide people up into categories, and then judge those categories. So, in the end, there are those who are like us and others. These others might be frightening to us. They might just be perplexing to us. Or they might somehow seem wrong to us.

In the first century, as the church was yet small but growing fast, who should belong was still an open question. But it was becoming increasingly clear that many different, diverse peoples were going to belong. Among those who gathered to worship, there were differences in race and culture, which would not easily be erased yet must be overcome. No longer, in the church, would there be the circumcised and the uncircumcised, but there would be one body in Jesus Christ.

These issues are raised in many of the New Testament epistles, seeming to indicate that this was a common problem at the time. The Spirit of God was crossing over boundaries and drawing diverse groups together in Christ – but those people were, maybe, a little averse to being drawn together. They were too preoccupied with their differences, and the ways those differences made them uncomfortable with one another. And in their own ways, they were prone to judging those who were different.

There were the poor Christians, some of them even slaves, and the wealthy Christians. They had dramatically different lifestyles, obviously. And the wealthy ones were sometimes unable to comprehend the unique challenges of the poor ones.

We have to admit that we are still beset by these kinds of problems. It is hard for us to understand people who are different from us. For those who abide strictly by the law, it is hard to understand the law-breakers. For those who are free of addiction, it can be hard to understand those who suffer under the weight of addiction. For those who have enough, or more than enough, it can be hard to understand those who don’t have enough and, to our minds, do a poor job of managing what little they have.

Put simply, it can be very hard for us to understand those whose path through life has been different from ours. In some cases, we admire them; in others, we disapprove of them. sometimes we are simply appalled by them.

Philip Yancey, in his book called What’s So Amazing About Grace, relays a story a friend once shared with him. A young woman came to his friend in desperate straits. A miserable sinner without a shred of dignity left, she was an addict, homeless, a mother of a two-year-old girl. She had no money and no food. She unloaded on this man a torrent of words, confessing to him all the horrible things she had done, all the horrible things that had been done to her. He listened, then he asked if she had considered going to a church for help. She looked at him with shock, and said, “Why would I do that? I feel terrible enough about myself already. They would just make me feel worse.”

To be truthful, I am afraid if I had been sitting across from the woman Yancey wrote about and listened to all the things she confessed, the thought would have entered my mind, “How could anybody do that?” And it is possible I would have judged her, condemned her, proving to her that yes, the church is there to make you feel bad about yourself, just in case you don’t feel bad enough already.

Any time we start a sentence with the words, “Why would anybody …” it is a chance to stop. Pause. Think about what it is we don’t understand. And then perhaps rephrase the question: “What kinds of circumstances might cause me to do such a thing?”

The reason Yancey told this story is because he couldn’t help but see the contrast between this young woman’s relationship with the church and Jesus’ relationship with sinners. Particularly, the stories about some of the women who came to him, miserable sinners without a shred of dignity. They were accustomed to being scorned by the religious establishment, but they looked at Jesus and saw someone they could turn to. They saw someone who would have compassion for them. Even though, as Paul wrote, he himself was sinless, Jesus put no barriers between himself and all the sinners of the world.

When we think about what the church is for, it is worth noting that it is sometimes called a hospital for sinners. No one, no matter how deep their transgressions, should be turned away from the church in their time of need. No one, no matter how appalling their sins, should ever be turned away from the church because of them. Remembering that we, too, are sinners and have found sanctuary in the church, where Christ heals us of the sickness of our souls. How could we not extend that same grace to others?

The radical thing that Jesus Christ did in his life was to draw the sinners and the outcasts to him. He healed those who had been cast out of society, giving them a chance to become reconciled with society, an opportunity to be restored to wholeness.

The letter to Ephesians speaks to the gentiles, saying you who were once far off, or aliens, have been brought near, by the blood of Jesus Christ. You who were once excluded: the gentiles, the women, the blind and lame and deformed, the sick, the imperfect. Now the walls and barriers have been removed, the gates are open. In Christ, all have been brought together.

For in him we find our peace. There becomes a whole new way to find and articulate our identity – and a whole new way to frame our outlook on the world.

You see, where we once looked at the world as a framework of lines dividing peoples into groups, separating them from others, we found our identity by focusing on the lines and what they represented: differences in acceptability, differences in belongingness. The lines represented the ways we differed, and we defended the boundary lines because they defined who we were against who we were not.

But in Christ everything changes. And we no longer look to the boundary lines, but we look to the center, which is Christ. The holy of holies. He is our center, our purpose, what we are drawn to, where we find our peace. He is our peace.

And so in Christ the circumcised and the uncircumcised came together. The slave and the free, the Jew and the gentile, the north and the south and the east and the west, all came together to find their peace in him. Turning our attention away from the lines that separate us and toward the center which now defines us.

May it be so.