When my children were young and we had a full house, I felt like I was always counting. If we went out together, literally counting heads to make sure everyone was there, no one was lost. At home, whether cooking, doing laundry, reading a book, or watching TV, I would at random moments make a count in my head. One is upstairs in her room, one is sitting at the computer, one is right here with me, and one is at the neighbor’s house. So, I understand the sheep owner, counting his sheep. You won’t just naturally notice that one out of 100 is missing. You would have to count.

When my children were young I also had the horrible experience of losing one of them. In the mall, to my recollection. More than once. So many things to look at, so many places to hide or wander off to. Yes, I was the reason the mall went on lockdown more than once.

Losing someone is a very distressing feeling. And, if Jesus is actually talking about humans in this parable of a lost sheep, then I get the urgency of the matter. When someone gets lost, especially someone vulnerable, there is a sense of urgency about finding them.

We don’t forget a loved one who is lost to us. Whether it is a soldier who goes missing in action, a teenager who runs away, or someone who gets picked up one day by the authorities and whisked away, “disappeared,” not to be seen again. Each one is somebody’s beloved, and they do not forget them.

No price can be placed on a human life; no statute of limitations can be applied to the effort to bring justice or reconciliation. So if this is what he’s talking about, the search for a lost child of God, I get the seriousness of it. At the same time, though, I have a problem with this parable.

The nature of a parable is to pull the listener in to the story. It’s a powerful teaching tool because it doesn’t just tell you something – it allows you to experience something. Draw the listeners in with some familiar scenario, something they know.

This is why Jesus’ parables so often used tales of farmers or shepherds – these were the things his listeners knew best. So this is what he gave them, and they would think, “Ah, yes! Sheep. Vineyards. Planting and harvesting.” They can see it, feel it, smell it, hear it. They know it so well they can even anticipate what will happen next. Give them some content that they can really engage with, something they are sure to have an opinion about, and then throw a curve. Give them a surprise, something new to chew on – this is how the parable works as a teaching tool.

So in this story, Jesus uses the old “which one of you” technique. Who among you would not do this? The subtext is this: you all are responsible, intelligent men and women. Which one of you would not do such a simple and obvious thing as this? And if you would do this, then how much more would your Father in heaven do?

He uses this approach in other places, too, such as the “who among you would give your child a stone if he asked for bread? If you know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven do for you.” It’s logical. It makes sense. It gets the message across.

But imagine how it might work in this case. Speaking to people who understand shepherding even if they are not shepherds, Jesus proposes to them, “Which one of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them, does not leave the 99 and go in search of the one that has gone missing?”

The bait here is the phrase “which one of you.” It says of course, it goes without saying, that you would do this thing, that this is the right thing. “Which one of you would not!” But then you hear this: “which one of you would not leave the 99 and go in search of the one.” Who, indeed, would do that?

What will happen if you leave the 99? You put them at risk. You abandon them to the wolves. Who, indeed, would do that? The very idea!

So, there you are, listening to Jesus’ story. You’re nodding along as he speaks. Then suddenly you stop nodding, and you’re thinking. Would I do that? Should I do that?

Jesus has left me feeling a little off balance. There is now a tension between what I have always known to be the right thing and what I hear Jesus suggesting to be the right thing. I am feeling less sure of my convictions now – and that might be okay. But I am also left with the uneasy feeling that I am perhaps unable to be the person Jesus seems to expect me to be.

Because I have tried to be that shepherd who goes after the one sheep who wandered away. I have tried. I have tried to be the savior who flies out over the landscape and seeks the lost and swoops them up, carrying them back to safety. I have tried launching rescues boats, standing at the helm, back turned to the remaining 99, who are left to feel abandoned, hurt, unloved and neglected.

I have been the one who believes against all the evidence that she can make that one wandering sheep change against their will; that the sheer force of my will, my love, my good intentions, can override the wandering sheep’s will.

I have tried to be the shepherd. But I am not that Shepherd. There is only one Good Shepherd.

It turns out that no matter where I am sitting, I am one of those sinners. One of the lost, actually. If I am a Pharisee or Scribe standing in judgment of others, if I am a tax collector taking advantage of others, or if I am just one of the generic, garden-variety sinners, I find that I am lost here.

Sometimes, especially when I am least able to acknowledge my own need, I am lost.

And in those moments, I need Jesus to notice that. I need him to drop everything and pull out all the stops and come find me, bring me home.

Perhaps the message of this parable is not that we are good and God is better, but that God alone is good. And we are sinners – sometimes lost, sometimes found, always in need of repentance.

All of us are among the lost at times. Yet all of us are the ones who need to be looking out for the lost. How can we keep alert, to see who among us is overlooked, who is at risk of becoming truly and irreparably lost? And how can we be the hands and feet of Jesus, doing what we can to bring them home?

Deb Rossi, who is the director of HOPE, told me recently about her new project. She has recently received funding to help men and women who are being released from incarceration to re-enter society. She shared with me the simulation she recently participated in to demonstrate just how challenging it is for someone returning home after prison. She was given an identity, which looked pretty strong on paper. Someone who had more resources than many who are coming out of prison. But I was surprised to hear that she was defeated by the challenges of re-entry. Given four chances to do it successfully in the simulation, every time she ended up back behind bars.

These ones who are among the lost need as much help as we can give them, for a chance to feel redeemed. Found.

The power of finding and saving the lost is not ours. But seeing them, welcoming them somewhere in the midst of the extremes; enfolding them in the love and care of community actually is in our power.

And when we do that well, we are a little less lost, a little more found, too.

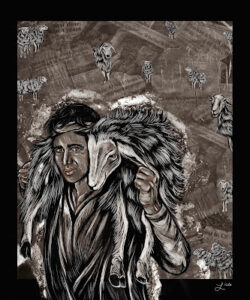

Picture: Lost & Found by Lisle Gwynn Garrity, A Sanctified Art, LLC